A shorter version of this essay appears in the Autumn 2013 issue of the beautiful, creative online magazine Soiled and Seeded. Here Katherine and Jeanne explain the topological relationship between figs and mulberries and do a little investigative journalism.

Mulberries

Figs and mulberries are both gorgeous, sexy fruits, but in very different ways. At first blush a mulberry could be the fragile hot-mess cousin of a blackberry, while figs are classically sensual fruits, like marble nudes teetering on the edge of vulgar. For all their fleshy assertiveness, both fruits keep their secrets; and it takes more than a long, intense gaze to uncover their close relationship and know what makes them sweet. Mulberries may look like blackberries (and share a taxonomic order), but they are built from different plant components. The true siblings are mulberries and figs (both in family Moraceae), and at heart they are very much alike, although figs are clearly the more introverted of the two.

Anatomy of the Moraceae

To understand a mulberry or a fig, you first have to recall the basic structure of a flower and imagine the various ways flowers can be grouped on a plant. Both figs and mulberries cluster their tiny flowers together into dense and well-defined inflorescences. And, in both, all the flowers on an inflorescence then develop into a single fused unit, which we casually call a fruit. Before offering the details of what we eat we’ll need to look at the individual flowers and fruit.

An idealized flower has four concentric rings of parts, or whorls. From the outside in, they are:

1) usually green, modified leaves, called sepals (collectively the calyx), which are prominent in the nightshade family and persimmons;

2) often colored or otherwise showy petals (together called the corolla);

3) the “male” stamens, consisting of a filament holding aloft a pollen-filled anther; and

4) one or more “female” pistils, anchored by an ovary. The pistil catches pollen grains, which then grow down through a style to the ovary and the seeds within. The ovary matures into a fruit.

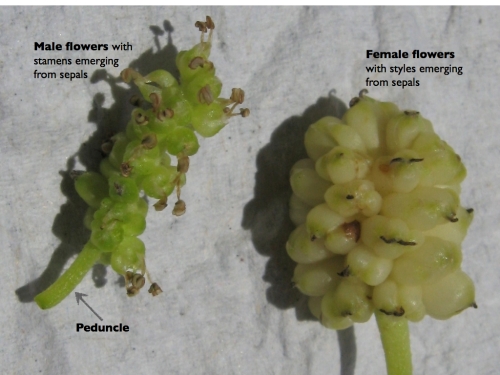

Not all flowers have all of these parts. Figs and mulberries make separate flowers with only one or the other sex: “female” flowers lack stamens, and “male” flowers lack pistils. Both female and male flowers also lack petals. So, for example, a “female” mulberry flower will have only sepals and a pistil, and a “male” flower will have only sepals and stamens. Male flowers therefore cannot make fruit just as female flowers cannot make pollen.

Mulberry inflorescences

Mulberry flowers are not large or showy, but they are visible. Fig flowers, by contrast, cannot be seen without opening up the structure that encloses them. As it turns out, being hidden from view also means being hidden from all but the most specialized pollinators, which is a big part of the fig story (see below).

Under a magnifying lens, mulberry and fig flowers are remarkably similar. However, their stories diverge as the flowers are pollinated and their fruits develop.

Fruiting bodies

Tiny mulberry flowers make miniscule fruits; by sticking together across the entire inflorescence, they masquerade as one large fruit and probably enhance their power to entice birds and improve their dispersal efficiency. But that’s not the mulberry’s only beauty secret. Strictly speaking, mulberry fruits are not that attractive. They are hard dry achenes with the appeal of a grain of sand. To make themselves sweet and juicy, they plump up the only other flower parts they have—their sepals.

Mulberry flowers becoming fruits

This is in contrast to blackberries, denizens of the rose family (Rosaceae), whose flowers, fruits and seeds are structurally distinct from those of mulberries (see figure below).

Click to enlarge. A-C Blackberry. D-F Mulberry. Mulberries resemble blackberries, but blackberries derive from a single flower with multiple fleshy ovaries, whereas mulberries derive from multiple flowers, each with a single hard ovary and fleshy sepals.

A fig is essentially an inside-out mulberry, an entire edible flower cluster hidden down inside its own stalk. This stalk, the peduncle, is the delicious bulk of what we enjoy when we eat a fig. To understand how we get from mulberry to fig, it is useful to reconstruct (approximately) evolution’s recipe for figs. Imagine a mulberry inflorescence, give it a long peduncle, and mentally expand the entire axis into a globe. All of the flowers should be above the equator, with the peduncle below it. Pull outwards on the equator, flattening the globe into a disk with all the flowers on top and the peduncle constituting the underside. There are members of the mulberry family (e.g. Dorstenia) whose inflorescences take this shape. Finally, curve the disk upwards into a bowl, then into an urn, and finally into a sack. All the flowers will be inside the sack, completely surrounded by peduncle tissue. The entire structure has a specialized name: syconium. (Interested readers may look up the not-safe-for-work etymology of “sycophant,” from the Greek for “showing the fig.”)

Cutaway view of a fig with a closeup of a female flower on the left. Flowers within the fig are shown without a calyx, which is not apparent anyhow.

Fig flowers are even smaller than mulberry flowers and likewise make gritty little achenes for fruit. They are attached to the inside of the syconium by flower stalks (pedicels), which get very soft as figs ripen. The sweet part of the fig is a combination of peduncle, pedicels, and sepals. The crunchy parts are the achenes. But what about the old legend that wasp parts add a little something to the texture?

Are there wasps in my Newtons?

Usually, before fruit can ripen, flowers must be pollinated. Mulberries are simply wind pollinated. However, in most of the more than 800+ fig species, pollination is courtesy of small wasps from the Agaonidae family. Figs and agaonid wasps have required one another for existence for at least 60 million years. And like many co-dependencies, this one isn’t pretty. Fig seeds feed wasp larvae. A large family of newborn wasps synchronously emerges from the seeds within a syconium. The wingless, blind males have two quick duties before dying: inseminating their sisters and chewing escape holes for them. Before leaving home, young females gather pollen from male flowers. A winged female has 48 hours to find and enter a new receptive fig, pollinate the flowers, and lay eggs. The fig doesn’t help her. The only opening, the narrow ostiole, is defended with sharp bracts. With specialized jaws and a strong head, she chews her way past this gauntlet and into the fig, but tears her wings and antennae in the process.

The ostiole defended by sharp bracts.

Figs make two kinds of female flowers: long-styled and short-styled. Wasps can lay eggs only in short-styled flowers, but they are able to transfer pollen to all flowers. The short-styled flowers thus make wasps, whereas the long-styled flowers make fertile seeds. Under this arrangement, both the plant and the pollinator may reproduce. The mother wasp dies after her tasks are complete and fig enzymes devour her body during ripening. The spent male offspring meet the same fate, while their gravid sisters fly off to other figs.

About half of fig species come in two different sexes: “male” plants are similar to those described above, and their syconia bear both male and short-styled female flowers. (The ovaries of the female flowers serve mostly as wasp nurseries, so they tend to be forgotten by fig sexers.) “Female” plants produce syconia containing only long-styled female flowers, and the poor wasp entering one of these cannot lay eggs before dying. Although her own reproduction is thwarted, she brings pollen from a “male” plant that triggers seed and syconium development. Some favored varieties (e.g. Calimyrna) fall into this category and are called gynodioecious. Because they are pollinated, they produce viable seeds and a large sweet fig syconium, but their long-styled flowers preclude egg-laying, and we avoid a mouthful of baby wasps.

Mission fig showing its ostiole

Some mutant fig varieties can ripen syconia without pollination. These parthenocarpic (“virgin fruit”) plants have been propagated asexually by humans for over 11,000 years and comprise most of our edible figs (e.g. Mission and Kadota). They may lack well-developed seeds, but their achenes provide some crunch and their flesh is free of liquified female wasp body.

So are there wasp bits in your Newtons? It depends on which fig variety the good people at Nabisco use for their iconic cookie. This seems to be a trade secret, though, as the label simply lists “figs.” We decided to investigate. The most common varieties used for fig paste include the wasp-free parthenocarpic Mission and Kadota and the female-trapping gynodioecious Calimyrna. Calimyrna figs reportedly have larger achenes than other varieties, and we further reasoned that their achenes would contain well-formed seeds, whereas Mission and Kadota achenes would not. We did not have any Kadota figs handy but were able to compare Newton filling to fresh Mission figs.

We discovered right away that the image on the box, which shows a filling rich with achenes, does not match the grit-free filling in an actual cookie. The filling seemed suspiciously smooth, and after extensive searching, we found only 19 achenes in an entire cookie. It is possible, then, that the achenes we found slipped through the (postulated) strainer mesh and don’t represent the full achene size distribution of the mystery variety. In any case, they were no larger or smaller than Mission fig achenes. When we opened up the Newton achenes with a razor blade, we found what looked like a small seed inside each one. We were getting somewhere, as this suggested the Calimyrna variety. When we opened up the Mission achenes, though, we found them filled with something very seed-like as well. As it turns out, at least according to a few older papers, parthenocarpic figs such as Missions can make seeds full of nutrititive tissue (endosperm), even though they lack actual embryos. Alas, we found no evidence in favor of one fig variety or another.

It may be comforting to know that there would be no baby wasps in filling made with any of these varieties. If the filling came from Calimyrnas, any female wasps would have been digested before the figs were even harvested. We probably should be more worried about a fruit fly floating in our chardonnay than a wasp in our Newtons. While perhaps small comfort to the squeamish, the rest of us fig and mulberry enthusiasts can toast the wasps and the wind before digging into a plate of figs roasted with basil and cheese–recipe below.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Quentin Cronk for correspondence about the morphological delimitation of peduncles.

More information about fig pollination may be found at the wonderful site Wayne’s Word

Roasted figs with basil and cheese

Slice fresh figs lengthwise and bake at a high temperature (400º F) until they bubble. When they have cooled just slightly, top each with a small basil leaf and a nubbin of rich soft cheese (a triple creme, for example).

Link:

Very informative and impressive post you have written, this is quite interesting and i have went through it completely, an upgraded information is shared, keep sharing such valuable information. Flowers and Fruits Plants

ResponderExcluir